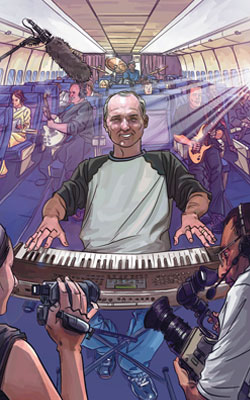

Some travelers “collect” restaurants, others take in major-league baseball games. Many an avid golfer expands his life list of postcard-perfect golf courses. Kincaid’s passion is music. As a boy, he practically wore out his Elton John records learning to play “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” and “Daniel” by ear on the piano. These days, he moonlights as a keyboardist and vocalist in a rock and blues quintet, a bar and party band that happens to include two Delta pilots and another member whose livelihood is linked to aviation. The band’s name: Flyer (www.flyer-band.com). When Kincaid travels, his quest is musical. “You can discover some great music if you’re willing to get off the beaten path and into some small, intimate places,” he says—often, music from up-and-coming local bands or solo performers that you won’t hear on commercial radio. He starts by ignoring the preset buttons on the radio of his rental car. “Most cities, it’s the same old stuff,” he says. “But when I go to San Francisco, I immediately dial in KFOG; in Chicago, WXRT. There’s a great station in Annapolis [Maryland] called WRNR. In Tampa [Florida], I listen to WMNF. It’s kind of like a hunt, finding something that’s different. I love discovering music that I hadn’t heard before, music that isn’t being corporately pushed or shoved down your throat.” Whenever possible, Kincaid tries to take advantage of his business travel by getting to see some of these artists live in small, out-of-the-way clubs. “If I go to Memphis [Tennessee], I’ll go to Beale Street and listen to a blues band. There’s a great jazz place in London called Ronnie Scott’s,” he says. Nowadays, with the schedules of most bands available at their Web sites, he’ll generally check to see if an upcoming trip happens to land him in a city when one of his favorite bands, maybe Sonia Dada or The Blind Boys of Alabama, will be in town. He’s seen Sonia Dada four times—once at a bar while vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, where who should sit down beside him but Keith Richards, effectively validating Kincaid’s taste in music. Onstage himself with Flyer, Kincaid is proud of the band’s musical range: “Flyer covers 40 years worth of classics: ‘Moondance,’ ‘Brown Sugar,’ ‘Mustang Sally,’ ‘Layla,’ ‘Steppin’ Stone,’ ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ and ‘Dream On,’ as well as [songs by] recent bands like Widespread Panic, Train and Foo Fighters.” Flyer’s lead guitarist, Mark Bradley, and its rhythm guitarist, Lex Lauletta, are not only Delta captains but also senior instructors—Bradley for Boeing 767s, Lauletta for 737s. Drummer Neil Johnson is a Lockheed Martin senior manager with the team building F/A-22 Raptor stealth fighters. And new bassist Richard Banks is an executive with SmartTrust, a Swedish company that makes software for the mobile-phone industry. The band typically practices once a month and performs twice a month—be it at a bar, wedding or party, or as a warm-up band for country music group Sawyer Brown. Late night or not, each gig helps Kincaid recharge his batteries, helps him balance work/life issues. Music, he’s found, provides the perfect counterpoint to putting his Ph.D. in clinical psychology to work parsing the management skills and track records of successful executives. “I’ll assess the individual on all sorts of personality characteristics,” Kincaid explains. “They spend about eight hours with me, starting with doing questionnaires online or about two to three hours in a face-to-face interview with me. No matter the industry, no matter the job, one of the things that I’ve seen that contributes to success is a very close alignment between how you see yourself and how others see you. Tools like 360-degree feedback are designed to help close that gap.” Almost always, he’ll ask, “What’s the biggest misunderstanding that people have about you?” Warning bells goes off if the answer’s something like, “What do you mean? People don’t misunderstand me. I’m very clear, very direct.” Kincaid’s work has also identified a recurring differentiator in the careers of successful top executives. “You come into an organization, you start to rise. At some level you peak,” he says, drawing a rising curve that flattens as it moves to the right. “What I’ve noticed is the first part of that curve is almost always about results. Did you get the sale? Did you hit your numbers? You start climbing the ladder because of results. “But then you get to a point in your career where everybody around you gets results. It’s no longer a differentiator. The people who couldn’t get results peaked earlier and are in lower-level jobs. You’ve risen to a level where what differentiates people is relationships. It’s both political—who you know and how you know them—but it’s also about how well you use those relationships. And relationships have a lot to do with an alignment in how you see yourself and how other people see you, how self-aware you are.” Delta, in fact, helped provide Kincaid with an unforgettable lesson in self-awareness—and a story he often tells in executive coaching sessions and public speaking engagements. A couple of years ago, in advance of a flight from New York to Los Angeles, he got a call from the airline. Delta’s ad agency was gathering focus-group data from Delta BusinessElite travelers. Would Kincaid be willing to be filmed by a camera crew from the time he left work on the Friday afternoon to his arrival that night in L.A.? He agreed on the spot. He was accompanied by the crew to John F. Kennedy International Airport. He was interviewed about all aspects of the trip: the check-in process, the food, the inflight movies, comfort in business class. As he walked through JFK with a camera crew, heads started to turn. On the plane, passengers kept asking the flight attendants, “What’s going on? Who’s that?” Kincaid recalls feeling—and relishing a little—a sense of self-importance. That is, until he arrived at the airport in Los Angeles. The camera crew had preceded Kincaid to the gate area. As he was schlepping his bags off the plane, he saw not only the camera crew but also a crowd several deep. “I’d failed to think about what happens when a camera crew sets up in L.A.,” Kincaid recalls. Eyes stared. Voices murmured. And faster than you could say “nobody,” the palpable buzz morphed into a collective groan. “No matter how confidently I walked off that plane, I was not a movie star,” says Kincaid. “I use this story with executives as an example of the difference between how you see yourself and how others see you.” —John Grossman

|